Breath – the ultimate tool of human creativity.

This is a bold statement, but our world would look very different without the 22,000 movements of air that our muscles generate every day through repeated contraction and relaxation. And our social world would be impossible without it. Our speech exists only because we learned to constrain the air flowing through our oral cavity. Unlike our closest primate cousins, we have high palates that allow for all sorts of vocal combinations that our ancestors exploited for ever more complex symbolic value.

Just as we learn our first language and begin to manipulate the flow of breath for the sake of communication, we can also learn to develop our capacity to modulate the passage of air for other purposes. This power is easily available to all of us, yet the vast majority of mankind passes through life without tapping into this potential. Worse, without even realizing that it can be tapped into.

Breathing constitutes one of the cardinal motions involving our body. While external body movements operate primarily along the front/back and right/left axes, and posture can improve alongside the up/down axis, breath constitutes the prototypical function alongside the in/out axis of our bodies.

The fact that the airflow represents an interface between our inner physique and the surrounding universe has attracted the attention of mindful individuals. In many cultures, breathwork became an inherent feature of a variety of practices aimed at spiritual awakening and spiritual development. Although such practices are often associated with oriental philosophies, special breathing techniques have been practiced in many other cultural contexts. Today, yogis and athletes, monks and navy seals, woodwind players and martial artists, singers, and public speakers all recognize that breathwork is the key to the art of moving energy throughout the body, improving its performance and focusing on other Aspects of Being.

There are two broad approaches through which one can work with the breath. The first approach involves increasing one’s Breath Awareness, which is achieved by simply observing one’s own breathing. The second one is breathwork/conscious breathing, which can be practiced through various techniques, each of which aims at achieving specific results.

Let’s start with the first approach:

Breath Awareness

Breathing consists of several basic components, which we learn within seconds of coming to this world and, short of contracting a respiratory disease, we tend to take it for granted ever since. It is the only vital bodily function that is, at the same time, automatic and unconscious but can also be controlled. And yet, it remains largely neglected by most people. While only advanced Yogis can control their heartbeat or digestion, all of us can learn to observe and then control our breath.

What is the main purpose of this awareness?

Paying attention to our own breath is one of the most straightforward techniques that help us focus on the present moment. Why is this? Because we can only observe our breath in the Now – not in the future or in the past.

If we bring our awareness to this vital activity, we will notice the complexity of this instinctive process. For example, when we breathe in through the nose, we can follow the flow of air, and feel the sensation of the air passing from the nostrils into the chest, and then filling the abdomen. We can conceptualize metaphorically the activated respiratory tracts as passages, connectors, and containers. We feel the expansion in the belly and are then free to decide whether to hold the air there for a moment, when to let it out and how fast.

Alternatively, we can let our breathing follow its habitual course. Observing the rhythm of our own breathing rivets our attention. It is almost impossible to closely observe the full cycle of our breathing function and let the mind wander at the same time. In other words – a single breath performed in a conscious way becomes a mini meditation, even if it takes only 10 seconds.

What is remarkable about this seemingly effortless activity is that this mini meditation can be practiced multiple times throughout the day, while waiting in line, walking in the park, driving the car, or listening to music.

Regardless of the situation, conscious breath brings more presence into our daily activities.

The straightforward nature of this focused activity may be helpful for those who are not experienced in meditation practices and appear resistant to the very idea of meditation. Rather than imposing a daunting practice of advanced meditation, the first step could consist in observing one’s own breathing. Most beginners are pleasantly surprised by the immediacy of the experience. They gain a new point of access to their Physical Aspect of Being.

The second approach is conscious breathing, i.e. Breath Control.

Breath Control

Conscious breathing helps to connect to other Aspects of Being.

- At the emotional level, it allows us to direct attention to our emotions and, at the same time, to balance the physical sensation associated with that affective state. When we experience unpleasant emotions, breathing offers instantaneous relief.

- At the cognitive level, it helps us dispel the self-chatter overpopulated with transitory thoughts, scraps of semantic material, and recurrent imagery.

- At the spiritual level, it opens the door to the Now, the present moment (more on this in the module devoted to the Spiritual Aspect of Being).

Our past emotional experiences become, over time, strongly intertwined with painful thoughts and fallible memories. Contrary to what we hear from some coaching methods, is extremely difficult to control those emotions by “changing one’s thoughts” and even more difficult to maintain such a “change”. For most people, simply thinking about emotions is not particularly conducive to solving their emotional dilemmas. On the other hand, conscious breathing proves helpful to shift away from the natural tendency to cogitate. It offers an alternative solution to the largely futile calls to “controlling emotions by changing one’s thoughts”.

Instead of “thinking” about the emotion, we learn to feel the emotion and breathe through it.

This simple act helps ease the tension in the body. This does not mean that breathing in any way “replaces” emotions. The emotion is still there. Rather, breathing is used to soothe the body and relax in the presence of intense emotions. In other words, this is not breathing “to make it go away”, but rather breathing to “allow it to be there”. What we experience in the process is the sensation of physical relief.

There is a simple physiological reason behind this relief mechanism. When one is overwhelmed by powerful emotions (“the tiger approaches”), the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) increases the state of alertness, and the rhythm of inhalation automatically accelerates. The body tenses up and our respiratory tract contracts – the throat is constricted, and choking may occur.

Sweating, trembling, and tearing are among other commonly observed bodily reactions. Other muscles contract as well – in the neck, the jaw, the forehead, the chest, the shoulders, and the abdomen. Some people may even experience cramps and feel “a knot” in the stomach.

By contrast, slow, controlled breathing provides an antidote to such contractions by activating the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), favoring relaxation and digestion. When slow, controlled breathing is used consciously, it is possible to learn to meet and greet whatever emotions arise.

These natural reactions can be mirrored and replicated by putting more emphasis on either inhalation or exhalation.

During the inhalation phase of the breathing cycle, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) facilitates the acceleration of heartbeats. During exhalation, on the other hand, the vagus nerve in the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) secretes a transmitter substance (acytelcholine) which causes deceleration of beat-to-beat intervals. Longer exhalation not only slows down the heart rate but, over time, also reduces blood pressure, improves mental focus, and helps deal with stress. The resulting relaxation is also conducive to lowering the levels of blood sugar, cortisol, and adrenaline.

By varying the length of either inhalation or exhalation, it is, therefore, possible to increase or decrease the heart rate.

Doing it Together

The power of conscious breathing goes beyond solitary practices. Originally, “inspiration” meant “breathing in”, but “con-spire” stands for “breathing together.” Many sacred rituals and religious ceremonies involve chanting, singing, and reciting mantras together, in unison. Such activities require that participants synchronize their breathing. Breathing together helps us to feel and to remember our connection with each other. Advanced life coaches know how to stabilize their client’s emotional state by gently synchronizing their breathing rhythm with the client’s. In forming future coaches, New York Life Coaching Institute places a lot of emphasis on such techniques, as one of the fundamental components of holding space for the client.

The Dimensions of Breathing

There is a great number of breathing techniques, many of which can be applied for specific therapeutic purposes. The large variation is due to a significant number of dimensions and possible permutations between them. Think about the manifold ways in which the simple act of breath can be described:

- Breathing through the mouth or through the nose

- Holding breath or continuous breathing

- Depth of breath (deep or shallow)

- The respiratory force applied to push the airflow

- The use of abdominal muscles

- The length of inhaling vs exhaling and the rhythm of each round

- The level of tension in the throat muscles

- The level and location of resistance imposed on the flow of air (in the throat, between the teeth, the lips, the raised tongue and the palate)

- Voiceless or voiced breathing (and, if voiced, the pitch)

- Specific sound effects (e.g., sibilant or using other fricatives, affricates, bilabial sounds, guttural sounds, trilling, wheezing, purring, snoring, grunting, groaning, or growling)

- Breathing dry air or generating saliva

Diaphragmatic Breathing

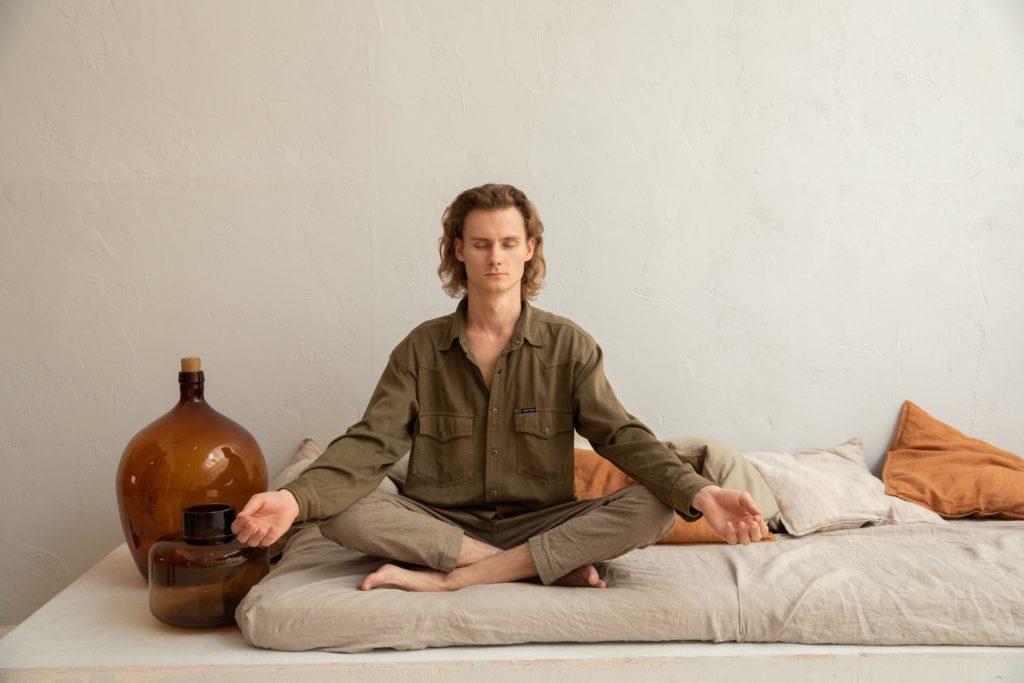

For those who are prone to anxiety, diaphragmatic breathing (Belly Breathing) is a great practice. Imagine the body as a container. The body is filled with air like the glass is filled with liquids – first breathing into the belly (the lower part of the container) and then into the “lungs” (the upper part). Similarly, when the air is let out, the order is akin to emptying the glass – first emptying the lungs (the top of the “container”) and then the belly.

It is ideal to be seated with a straight spine, the chin tucked in, and with the eyes closed. Face, neck, shoulder, and hands should be relaxed. Eyes should gaze at “the third eye” – the point right above the bridge of the nose. Place one hand on the upper chest and one hand on the belly, below the rib cage. Feel the belly expand when breathing in, and contract as breathing out. The hand on the chest shall not move very much. If the sitting position is challenging, it can be practiced by lying on the back and putting a book or a fluffy toy on the belly.

To avoid the problem of wandering thoughts, the attention could be directed internally to the body, and externally to the count of breaths. Yes, just counting the cycles offers the first gate to the meditative universe. It is as simple as that! Practice regularly until it becomes a habit. It helps to feel a lot calmer and grounded.

You can download our free guided breathwork MP3 here.